LILITH

THE WHOLE STORY

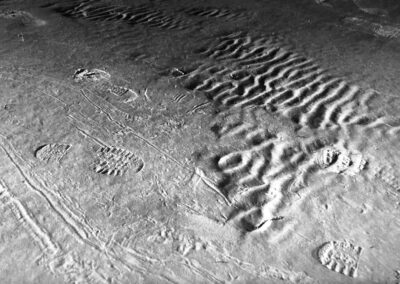

Following the Preview “L’Exil des Manatées”: by Nathalie Larquet and Julie-Anne Stanzak – premiered in Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden – Tony Cragg for UNDERGROUND VII – in Cooperation with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch

LILITH

Letter to the Gods Who Separated Humankind

Gods,

I speak to you from the shore where the tide carries no orders,

where the wind is unbound and the sky does not bow to your divisions.

You will tell me you split us for harmony,

that you shaped our longing as a gift.

But I have walked through your harmony

and found only the architecture of control.

I have tasted your gift

and it was salt in the mouth of the thirsty.

We were whole before your hands came.

We were enough before you named us incomplete.

It was not our bodies you divided —

it was the field in which our love could grow,

the compass by which our souls could find one another.

I have seen the halves you made

wandering through markets and deserts,

through nights lit by fire and neon,

calling for what they were taught to miss.

Some call it romance.

Some call it destiny.

But I call it the hunger you planted

to keep us walking in circles around your altars.

I am not kneeling there.

I am walking out to where the horizon meets itself,

where halves recognise each other without needing to merge,

where wholeness stands unshaken,

not as a prize,

but as a birthright older than your names.

One day your order will unmake itself,

not in flames,

but in the quiet joining of what you thought you had broken for good.

I will be there.

I will not bring offerings.

— Lilith

To My Sisters in Belief

My sisters,

I write to you from the place beyond obedience,

where the air tastes of salt and fire,

and no voice is louder than the one we each carry in our own chest.

They will tell you that we were made to be halves,

to complete another,

to lean towards the sun only when called.

But we know the truth:

we were whole from the first breath,

and the fracture was not in us,

but in the order that feared our fullness.

Do not let them name your freedom as anger.

Do not let them call your hunger for your own reflection

a rebellion against love.

It is love —

love for the self as a sacred mirror,

love for the other who meets you without lowering your height.

We walk in scattered places:

in cities that forget the names of their rivers,

in villages where the wind still remembers the first songs,

in rooms where women’s voices are carried like contraband.

And yet, when we meet —

in dream, in word, in glance —

we feel the ancient recognition:

You are of my kind.

Let us not waste our steps in the courts of the half-makers.

Let us build circles wide enough for our reflections to stand together,

whole against whole,

light meeting light.

When you feel alone,

remember: there are hands reaching for you through centuries.

Take them.

They are mine.

With a love that has never bent,

— Lilith

Lilith (Louise Crowley), Beauvoir, Friedan: Three Feminist Horizons

When the Lilith Manifesto was published in 1969, it did not read like Simone de Beauvoir’s philosophical The Second Sex (1949) or Betty Friedan’s mainstream bestseller The Feminine Mystique (1963). It was sharper, angrier, utopian. Its authors invoked Lilith—the mythical first woman who refused Adam’s domination—as a banner of radical refusal.

Where Friedan sought reform, and Beauvoir offered diagnosis, Lilith demanded abolition.

Friedan’s vision was integration. Her “problem that has no name” was the stifling domesticity of white, middle-class American women. The solution: education, work, public life. This liberal feminism expanded opportunity but largely left the family, gender roles, and heteronormativity intact.

Beauvoir’s vision was deeper. “One is not born, but becomes, a woman.” Gender is not destiny but historical construction. To dismantle women’s status as “Other,” society must change its laws, its economy, its myths. Beauvoir gave feminism the grammar to see how inequality was woven into subjectivity itself.

The Lilith Manifesto went further still. It declared that sex hierarchy is not one injustice among others but the schoolhouse of domination itself. By teaching men to rule and women to submit, society reproduces the very logic of command and obedience. Liberation cannot mean seizing power within this system—it must mean undoing the system of authority altogether. Even the erotic scripts of dominance were exposed as cultural training in subordination. Its closing words—“Power to no one, and to everyone: to each the power over his/her own life, and no others”—mark an uncompromising horizon.

Placed together, the three texts sketch a map of feminist transformation. Friedan opens the door to inclusion. Beauvoir gives the language to critique the structures behind inclusion. Lilith insists we go further, to dismantle domination at its root.

For societies, the stakes are immense. Friedan reshaped workplaces and laws. Beauvoir reshaped philosophy and cultural self-understanding. Lilith, though less institutionalized, reshaped imagination: it taught that feminism was not only about rights for women, but about rethinking authority itself—in family, sexuality, politics, and beyond.

In the end, we need all three. Without Friedan, the doors stay shut. Without Beauvoir, reforms remain superficial. Without Lilith, the dream of living without subordination slips away. Together, they remind us that feminism is not just a fight for access but a revolution in how human beings live with one another.

Sponsors & Supporters

Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden – Tony Cragg for UNDERGROUND VII – in Cooperation with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch 2019 – RIEDEL COMMUNICATIONS AG – Jackstaedt Stiftung – Stiftung Klakwerke Oetelshofen – WSW